View Post

‘…his manners were so exactly what they ought to be, so polished, so easy, so particularly agreeable…’

‘…it was all the operation of a sensible, discerning mind.’

‘His manners were an immediate recommendation…’

‘Everything united in him; good understanding, correct opinions, knowledge of the world, and a warm heart…steady, observant, moderate, candid…’

‘…There was never any burst of feeling, any warmth or indignation or delight, at the evil or good of others…She prized the frank, the open-hearted, the eager character beyond all others…She felt she could so much more depend on the sincerity of those who sometimes looked or said a careless or hasty thing, than those whose presence of mind never varied, whose tongue never slipped.’

‘…she had been mistaken…unfairly influenced by appearances in each; that because Captain Wentworth’s manners had not suited her own ideas, she had been too quick in suspecting them to indicate a character of dangerous impetuosity; and that because Mr. Elliot’s manners had precisely pleased her in their propriety and correctness, their general politeness and suavity, she had been too quick in receiving them as the result of the most correct opinions and well-regulated mind.’

Of all the brilliant insights in all the Austen books, this is the one that has influenced me the most. I’ve seen this play out over and over in real life. I’ve made the same mistake as Lady Russell in my own way, choosing people who meet my ideas of authenticity and honesty without considering that my mistrust of a certain kind of charm and suavity also translates into a bias towards a certain kind of person. I have recalled this passage to myself many times in my life, and it has often prompted me to evaluate people more fairly.

I consider Persuasion the softest, most romantic, and most melancholic (‘a sort of desolate tranquility’) of the Austen books. There’s an air of wistfulness that pervades this final work of hers. I imagine Austen on her deathbed at far too young an age, writing this meditation on love, loss, longing, and constancy. I wonder how much of it was borne of her own reflections on connections made and missed in her youth and through her short, constricted life. Persuasion feels sometimes almost like balm, like wish fulfillment, a hopeful second-chance story of rekindled love, unconscious fidelity and lasting romantic chemistry.

And yet, like all her other books, Persuasion is so much more than a love story. It has a gentle gravitas – all her books do, but this one is weightier – and it has those character insights that are almost startling in their depth and accuracy, in their ability to stick with you and return to you over and over for years.

This has always been my favourite of the Austens. Emma is livelier and more complex, Pride and Prejudice funnier and more exciting, but my heart has always belonged to unassuming Anne Elliot with her quiet intellect. There has always been something that touched me about this book, but it wasn’t until my most recent re-read that I realized how pithy and insightful it was.

‘She had been forced into prudence in her youth, she learned romance as she grew older – the natural sequel of an unnatural beginning.’

Of all the Austen heroines, barring Fanny Price, whom I’ve never liked, Anne is in the most unenviable position at the beginning of the book. Trapped with a vapid and insipid father and an even shallower daughter, at an age where she’s considered to have no prospects, with only the memory of a passionate but short-lived engagement, it seems like there is very little for Anne to look forward to in her life. Yet, she tolerates her situation and the disrespect she faces with an equanimity that could be, and is, mistaken for passivity. She makes the best of her circumstances, with a quiet security in her own worth. She is gentle to people who cannot see her worth, kind and comforting where she could easily be harsh or scathing, forgiving where she could be resentful. She is no Lizzie or Emma. Where they might be goaded into a cutting remark, Anne chooses to dignify the instigator with a sort of grace. Anne could have been a Mary Sue, but she’s saved by her intelligence and humour, though her audience is often only herself. Her constant kindness and refusal to ask for anything in return result in her being taken for granted by her family, her friends, even Captain Wentworth. And yet she knows her mind and possesses a quiet – there’s that word again – assurance.

“My idea of good company, Mr. Elliott, is the company of clever, well-informed people, who have a great deal of conversation; that is what I call good company.”

An entire cast serves to demonstrate Anne’s superiority of character. Henrietta and Louisa, Anne’s brother-in-law’s young sisters (Henrietta and Louisa), are introduced as ladies ‘who had brought home from Exeter all the usual stock of accomplishments, and were now like thousands of other young ladies, living to be fashionable, happy, and merry.’ Anne ‘would not have given up her own more elegant and cultivated mind for all their enjoyments’. She wonders later if it might not occur to Captain Wentworth ‘to question the justness of his own previous opinion as to the universal felicity and advantage of firmness of character; and whether it might not strike that, like all other qualities of the mind, it should have it’s proportions and limits…a persuadable temper might sometimes be as much in favour of happiness as a very resolute character.’ The resolute character, of course, being Louisa, contrasted here with Anne, who was persuaded by mother-figure Lady Russell to give up her engagement to Captain Wentworth. Her father and sister, Elizabeth, are vain, shallow, selfish and spendthrift. In Bath, Sir Walter ‘had frequently observed, as he walked, that one handsome face would be followed by thiry, or five-and-thirty frights; and once, as he had stood in a shop on Bond street, he had counted eighty seven women go by, one after another, without there being a tolerable face among them.’ They disrespect and even bully her. Mary, her other sister, though more appreciative, is a self-centred hypochondriac who doesn’t pay much attention to Anne’s needs and thoughts.

Captain Wentworth represents an environment where Anne is given her due. His friends and family are both far more liable to understand and appreciate her, being themselves of a higher intelligence and better temperament than Anne is accustomed to. Admiral Croft, who takes his wife with him in all his voyages, responds to Captain Wentworth’s squeamishness about having women aboard with:

“But I hate to hear you talking so, like a fine gentleman, and as if women were all fine ladies, instead of rational creatures. We none of us expect to be in smooth water all our days.”

This debate about men and women, their temperaments and their fitness for things remains a through line in the book. Anne’s capability – not only in the more traditional female role of the caretaker but also her clear-headness in times of crisis and in the face of high emotion and irrationality – are emphasized at multiple junctures. The turning point in the rekindling of Captain Wentworth’s regard for her is her handling of Louisa’s accident when he is himself overwhelmed. The others repeatedly turn to and rely on Anne for her good sense and rationality. Indeed, she often seems to possess these qualities in greater quantities than the men around her, in a way that belies her delicate and refined appearance.

The other great men-women debate in Persuasion is, of course, about constancy. In a significant conversation with Captain Harville towards the end of the book, Anne maintains that women’s feelings last longer, because they are confined to home and don’t experience the advantage of new environments and experiences. When Harville responds that books, songs and proverbs ‘all talk of women’s fickleness’ – of course, these were all written by men. ‘…the pen has been in their hands,’ as Anne says. She will not allow books to prove anything.

It’s interesting to me that Austen, that doyen of sense and unsentimentality, should propound that one never really recovers from, never forgets, love. I’ve always seen Austen as a sort of closet romantic. Yes, she writes love stories, but love stories bound in by class, endogamy, and good sense. Her heroines are eminently practical. Persuasion makes a case for abandoning this caution, but also for our susceptibility to “persuasion.” In the beginning, Anne listens to what appears to be good sense from her dear friend and mother figure, Lady Russell, and breaks off her engagement with the young, charming, intelligent Captain Wentworth. He is unequal to her in station, poor, and yet to prove himself. He is heartbroken and angered by her malleability. Anne suffers as greatly, but says later that she doesn’t regret listening to Lady Russell, that she would have regretted it always if she hadn’t.

Perhaps this is true. And yet, we see throughout the book how much Anne suffers for this capitulation. Captain Wentworth is able to throw himself into his work, to move in different circles, to make an attempt at moving on. Anne is forced to come to terms with this loss in unsympathetic and unconducive surroundings. Austen could not have made a more compelling case against the injustice of women’s limited environments if she had written a political treatise. Here, we see a woman with every natural advantage – beauty, intelligence, grace, kindness, relegated to the background and forced to interact with people who neither respect her nor can match her intelligence and perceptiveness.

Anne has only one true friend about her own age: an old schoolmate, Mrs. Smith. Mrs. Smith lives in tragic, straitened circumstances. At 31, she is already a widow, and a penniless one at that. She was used to affluence, now she has none. She has rheumatoid arthritis and is confined to a wheelchair in a small place with limited help. And yet:

‘…here was the elasticity of mind, that disposition to be comforted, that power of turning readily from evil to good, and of finding employment which carried her out of herself, which was from nature alone.’

Anne values her friend, who kindly took her under her wing after Anne lost her mother in school. She does not view her visits to her old friend as a favour or as bestowing charity, as her family views it. She genuinely enjoys the company of her friend, and is rewarded at the end by Mrs. Smith’s revelations about the true nature of Mr. Elliot’s character. Ultimately, Anne’s own kindness and steadiness of character save her – a fitting resolution!

The result of Anne’s debate with Captain Harville about the fidelity of men and women – who feels love more greatly, for whom it lasts longer – is Captain Wentworth’s heartfelt entreaty of a letter. A single page of passionate pleading, lines now forever famous:

‘You pierce my soul.’

‘I am half agony, half hope.’

I have loved none but you.’

‘A word, a look, will be enough to decide whether I enter your father’s house this evening or never.’

Captain Wentworth has always felt like an enigma to me. We don’t see as much of him as Darcy or Knightley or even Tilney. We hardly even see him converse with Anne. This is Anne’s book. This is in fact an incredibly effective tactic for conveying the enforced distance between them for much of the book. You feel the absence, the deprivation, the punishment, quite as keenly as Anne does. But in this one letter – in the space of a few words, our Captain reveals more character than most men do in a lifetime.

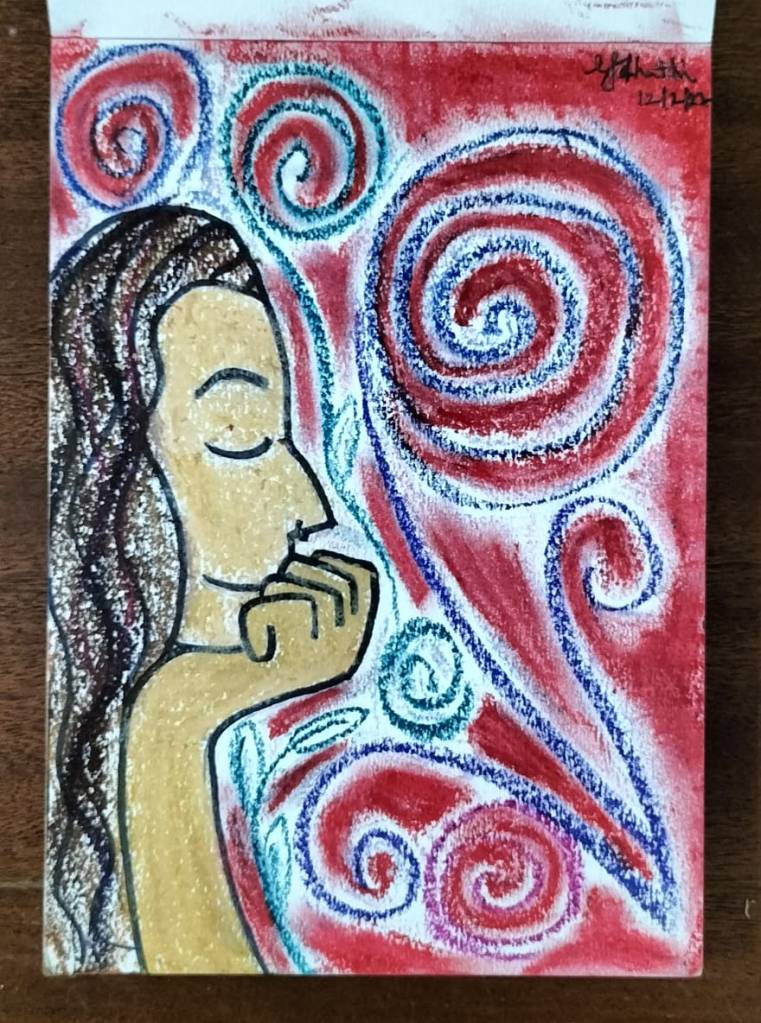

All ends well. Anne gets her happy ending. We rejoice in one of the most romantic letters written in fiction, the kind of letter every woman dreams of receiving. But for me, somehow, the melancholy doesn’t lift. I am left with that image of Austen on her deathbed, wondering how many other treasures existed in that brain, how many more characters she might have conjured with that deft hand, how much more she might have lived. How she could not possibly have known that an Indian girl would grow up 200 years later, venerating her, and learning about human nature from her precious manuscripts…